Check out our updated, more detailed description of list experiments here!

Consider this – you’re asked to participate in a survey and you dutifully agree (you responsible citizen, you). But you soon find out the subjects are...well...personal. You’re asked to share personal details from use of illicit substances to romantic history to opinions about unsavory topics. Is no topic sacred, anymore? If you fudged a response or two, you wouldn’t be alone.

Social desirability bias and preference falsification complicate self-report survey research, and that is especially true for sensitive topics. People feel pressure to conceal the truth for a variety of reasons, like social pressure, fear of reprisal, or a perceived lack of privacy. It is often difficult or impossible to determine the size and the direction of misreporting bias.

Some of the most important questions are also the hardest to answer. What is a researcher to do?

For sensitive political and cultural issues, Gradient employs list experiments.

How it works

A list experiment (also called the item-count technique) is a method for indirectly measuring private opinion for issues where individuals might otherwise be likely to publicly withhold their true opinion.

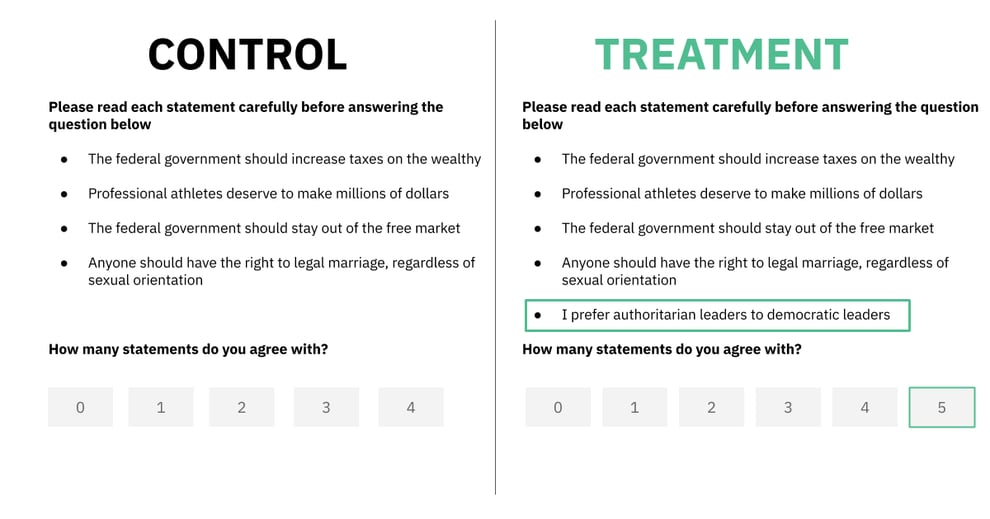

List experiments work by guaranteeing privacy. Unlike traditional survey methods, respondents are never asked to directly share their opinion about individual statements. Instead, respondents are asked to read a list of statements and choose the number with which they agree.

By comparing a group of people who see a list that includes the sensitive statement (i.e., the treatment group) to a group of people who see a list without the sensitive statement (i.e., the control group), we can make inferences about the prevalence of that private opinion in a population.

A typical list experiment question looks like this:

The prevalence of an opinion is cleverly devised through the randomization process, and is simply the difference in means between the number of endorsed statements by the treatment and control group. Recent advancements in statistics and multivariate modeling have led to more sophisticated analyses (Blair & Imai, 2012; Imai, 2014) allowing for more informative interrogation of the data.

List experiments in the wild

Shortly after the introduction of the coronavirus pandemic to the United States, we wanted to know whether Americans were really as worried about contracting the coronavirus as they were letting on. What we found flew in the face of public opinion polling and was, frankly, shocking.

Twice as many Americans reported their fear when asked directly compared to individuals who were guaranteed anonymity through a list experiment. Social desirability much? In a world full of social forces and media-driven narratives, a little privacy goes a long way.

When to use list experiments?

- When you want to learn about the prevalence of sensitive attitudes, perceptions, or behaviors

- When privacy is imperative for honest self-reporting

- When you want to know if there’s a gap between public and private opinions

- When you want to know who is more likely to withhold their public opinion

Comments