A list experiment is a method for indirectly measuring private opinion for sensitive issues where individuals might otherwise be likely to publicly withhold their true opinion. The list experiment works by guaranteeing privacy. Unlike traditional polling methods, respondents are never asked to directly share their opinion for individual statements. Instead, respondents are asked to read a list of statements and choose the number with which they agree.

By comparing a group of people who see a list that includes the sensitive statement to a group of people who see a list without the sensitive statement, we can make inferences about the prevalence of that private opinion across the American general population.

Example list experiment

In a list experiment, respondents are randomized into either a Control or Treatment condition. Both groups read a list of 4-5 items and report the number of items with which they agree, but do not specify the actual items with which they agree.

Both groups receive 4 identical items, but the Treatment condition receives an additional item for which we are interested in investigating. Therefore, the mean difference of items reported across the two groups is equal to the prevalence of that private opinion.

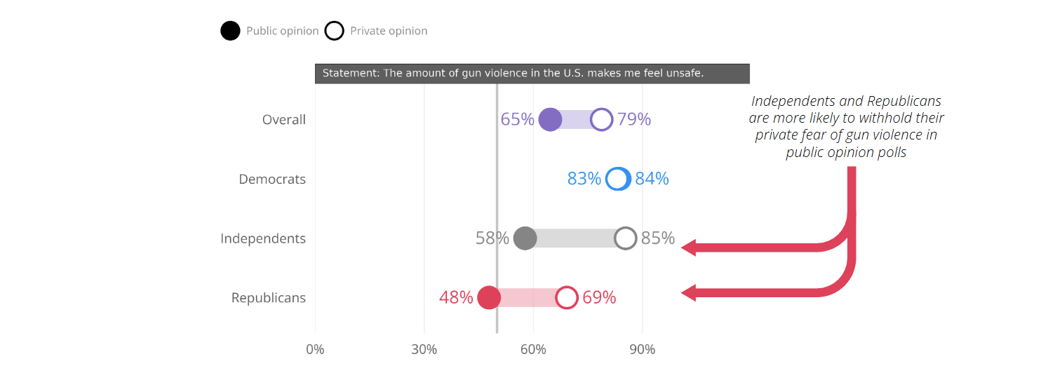

In the example below, the sensitive statement being investigated is "The amount of gun violence in the U.S. makes me feel unsafe"

Designing a list experiment

Below is Gradient's step-by-step guide to designing a list experiment, along with some other practical suggestions.

Step-by-step guide

- Identify sensitive statement(s) to be tested privately and publicly.

- Generate a pool of control items that are similar in length, format, and content as the sensitive statement(s).

- Administer the control items and sensitive statement(s) in a pre-test survey using a direct-question format.

- Assemble control item bundles.

- Carefully add a sensitive statement to each bundle.

- Design a survey with bundles of control items and sensitive statements, demographic and mindset variables, and direct questions for each sensitive statement

- Randomly assign respondents to control or treatment conditions.

- Collect data.

- Analyze results (see Analyzing list experiment data below).

Practical suggestions

Guarantee respondent privacy

List experiments are only as good as the privacy respondents perceive. If respondents have a reason to believe there is a way to identify their responses, they may feel a need to conceal their honest opinions. Floor and ceiling effects are major threats to the validity of results. If there is a tendency for respondents to agree with none of or all of the items in a list, their responses will no longer be considered private.

To reduce the threat of ceiling and floor effects, assemble bundles of 3-4 control items using the following principles:

- Include one high-frequency item

- Include one low-frequency item

- Include negatively correlated items

Assembling bundles that maximize the likelihood of respondents agreeing with at least one item but not all items is the surest way to maximize the number of respondents who believe their responses are truly private.

Use a large sample size

List experiments work, in part, by intentionally “adding noise” to the data. In other words, privacy is maximized (and thus social desirability is minimized), by making it harder to detect a signal. Therefore, list experiments require larger-than-conventional sample sizes to be more precise.

Align public and private opinion response sets

When a respondent evaluates a bundle of items, they are instructed to report how many statements they agree with. Therefore, direct questions must account for situations in which respondents agree with a statement, disagree with it, and when they have no opinion.

Include all three response options so that respondents aren’t artificially forced to agree or disagree with an item even when they have no opinion. Doing so runs the risk of biasing the gap between public and private opinion.

Conclusion

List experiments offer a valuable method for gauging private opinions on sensitive issues, bypassing the hesitancy often observed in traditional polling methods. By ensuring respondent privacy and employing careful design principles, list experiments allow for a more accurate estimation of private opinions within a given audience. Despite the inherent tradeoff between bias and variance, the evolution of statistical analysis in list experiments enhances their efficacy in uncovering private opinions and understanding the dynamics of public discourse.

Does your organization need to uncover the private opinions of your audience? Gradient can design a list experiment for you. Let us know how we can help.